Avian Flu Emerges in Unlikely Birds: A New Chapter in the Virus's Spread

Investigating the Changing Dynamics of Avian Flu Transmission in Birds

Avian influenza virus was recently detected in vultures at a local park in the little town where I live

Source: https://www.expressnews.com/hill-country/article/new-braunfels-bird-flu-detected-landa-park-20163134.php

I was dubious about avian influenza infection in vultures as I would think they would have hearty immune systems given they scavenge and eat dead animals. While vultures and other raptors are indeed exposed to a wide variety of pathogens through the carcasses they consume, their immune systems are specialized for handling those types of risks—primarily bacterial and parasitic infections.

So I turned to the scientific literature and found only a handful of journal articles on avian influenza virus infection in vultures.

The lack of scientific literature on avian influenza virus (AIV) in vultures may be due to a couple of reasons:

Ecological Niche and Low Exposure: Historically, vultures may not have been exposed to avian influenza viruses in large enough quantities to generate significant scientific interest. AIV is more often associated with waterfowl, poultry, and other migratory birds, which are more abundant and easily studied. Vultures are not typically the focus of AIV surveillance, and their role in AIV transmission may not have been considered a high priority in earlier studies.

Raptors and AIV Vulnerability: Raptors (which include vultures) are often less studied in the context of viral infections like avian influenza compared to other bird species. Raptors generally have lower population densities and may not congregate in large groups, making outbreaks in these species rarer or harder to study. Additionally, AIV transmission in raptors may be underexplored in the literature, especially since these birds tend to be more exposed to mammalian pathogens than to viruses like AIV.

Recent Increase in Outbreaks: With recent AIV outbreaks in various bird populations, including in vultures, it’s possible that the issue has only become more apparent in recent years. The introduction of more virulent strains, like H5N1, might be affecting a broader range of bird species, including scavengers that previously may not have been heavily impacted.

That being said, there was one journal article from 2007 documenting the first African outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1.

Researchers genetically analyzed influenza A (H5N1) viruses from Burkina Faso poultry and the first gene sequences obtained from African wild birds, 3 adult hooded vultures.

The first of these birds of prey had dyspnea and neurologic signs; the second showed asthenia and locomotion problems. While only samples from these 3 vultures were available for sequencing, an additional 45 hooded vultures were found dead or sick throughout Ouagadougou from February to June 2006; symptoms in these birds included diarrhea, respiratory disorders, prostration, apathy asthenia, and ruffled feathers.

However, another study published in 2012 was a serosurvey of raptors that prey or scavenge upon aquatic birds. Samples were taken from birds (n = 616) admitted to two rehabilitation centers in the United States.

In addition, samples from 472 migrating peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) trapped on autumnal and vernal migrations for banding purposes were also tested. Only bald eagles were notably seropositive (22/406). One each of peregrine falcon, great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), and Cooper's hawk (Accipiter cooperi) from a total of 472, 81, and 100, respectively, were also positive. None of the turkey vultures (n = 21) or black vultures (n = 8) was positive.

Beginning in January 2022, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) viruses have been detected in U.S. wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry and backyard or hobbyist flocks.

These are the first detections of HPAI A(H5) viruses in the U.S. since 2016. Since February 2022, nearly 159 million birds have died from AIV in the United States.

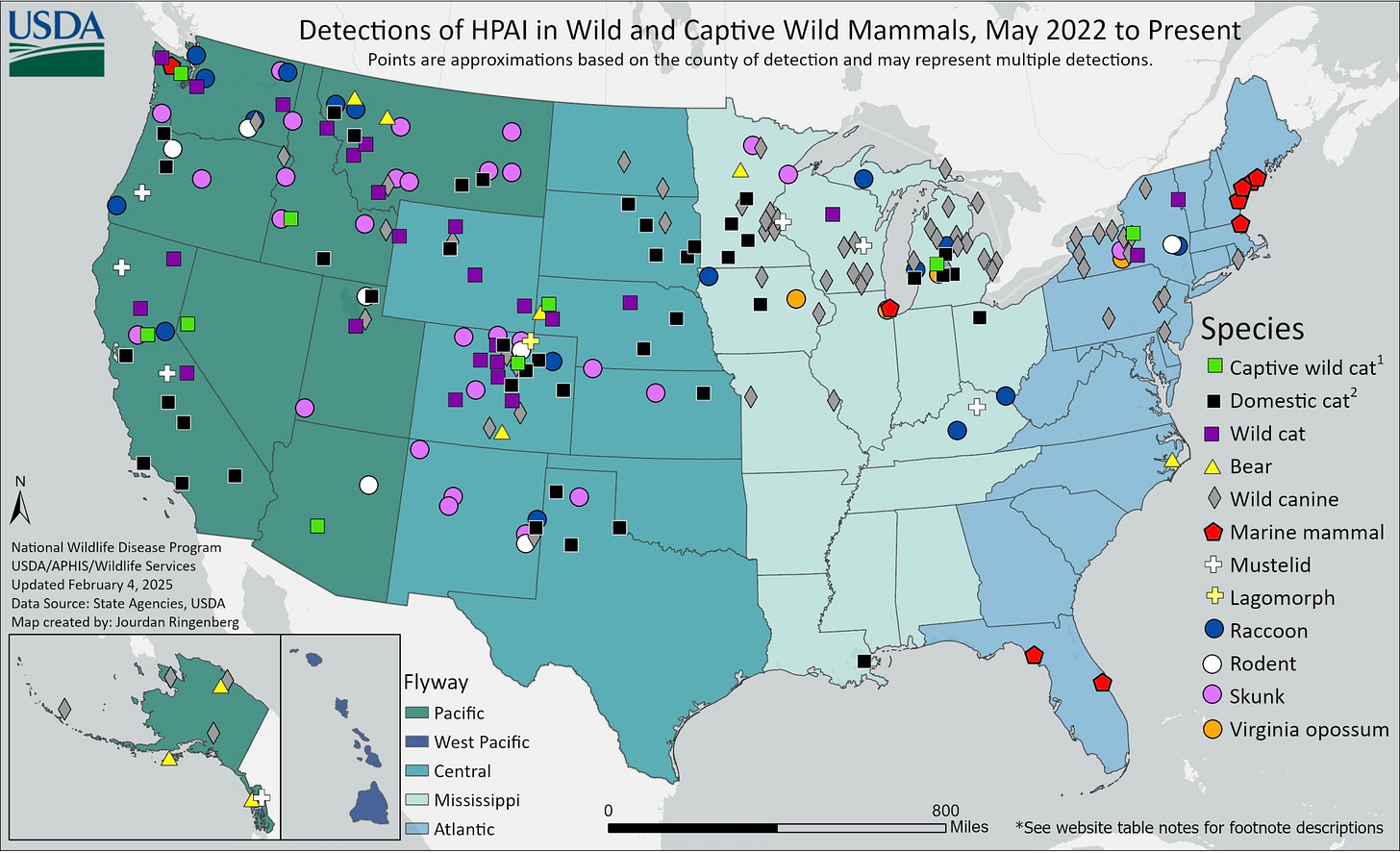

Avian influenza has continued to spread among birds and animals since it was introduced into the US in 2022

Since the introduction of avian H5N1 in US poultry, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) was first detected in U.S. dairy cattle on March 25, 2024. This is the first time this virus has been found in cows in the United States.

Here is a USDA website listing the animals and locations in which H5N1 bird flu has been identified in the US since 2022:

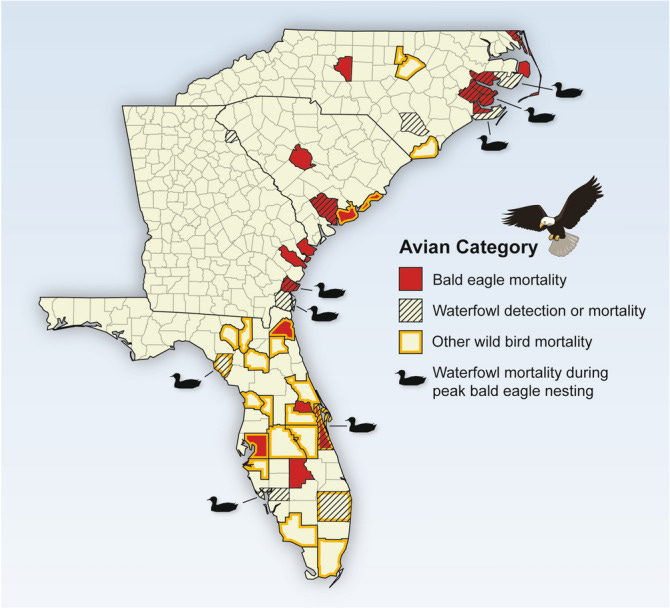

A recent journal article describes pathological findings of HPAI H5N1 in nine wild birds encompassing eight different species, including Accipitriformes (red-tailed hawk, bald eagle), Cathartiforme (turkey vulture), Falconiforme (peregrine falcon), Strigiforme (one adult great-horned owl, one juvenile great-horned owl), Pelecaniforme (American white pelican), and Anseriformes (American green-winged teal, trumpeter swan). All these birds died naturally (found dead, or died in transit to or within a rehabilitation center), except for the bald eagle and American green-winged teal, which were euthanized.

Since January 2022, HPAI-related mortality in bald eagles has been confirmed in 136 individuals collected from 24 U.S. states (as of June 10, 2022), including many along the southern Atlantic coast.

Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9813463/#CR8

Massachusetts has seen recurring incidents of bird flu among wild birds since 2022. Most recently, officials euthanized a bald eagle found in Townsend, MA that tested positive for the virus.

In 2023, California condors began acting lethargic and fatigued. Instead of the usual symptoms of lead poisoning, it was discovered the population had contracted the highly pathogenic avian influenza or bird flu.

“It was like we were losing a bird a day. So we lost 21 birds in three weeks,” said Hauck.

New strategy to combat avian flu, moving away from mass culling of infected flocks

Source: https://www.agweb.com/news/livestock/poultry/trump-administration-shifts-strategy-avian-flu

With egg prices in the United States soaring because of the spread of H5N1 influenza virus among poultry, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) conditionally approved a vaccine last week to protect the birds.

With the emergency vaccine approval 134 wild condors have been vaccinated by October 2024, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

But is vaccination the solution to controlling avian influenza outbreaks in the U.S.?

I’ll dive deeper into this topic in my next article.

Meanwhile they’re still swabbing away in bat caves trying to find the next pandemic.

Not sure how this is any different than GoF…because this is essentially how GoF starts.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00503-7

https://youtu.be/by0CvrQgosE