Tdap for insect bites? Tetanus Doesn't Spread via Mosquitoes

Separating Myth from Medicine: When You Really Need a Tetanus Shot

Tdap for Insect Bites: Do You Really Need It?

You’re outside enjoying a summer afternoon when an insect bites or stings you. It itches, it swells — but someone says, “Better get a tetanus shot!”

Is that really necessary? Let’s break it down.

Tetanus: Where It Comes From and How It’s Treated

Tetanus has been a well known disease for thousands of years. Tetanus, commonly known as lockjaw, is a serious bacterial infection that affects the nervous system, causing painful muscle spasms and stiffness. It is caused by Clostridium tetani bacteria, which is an anaerobic organism that thrives in the absence of oxygen.

The bacteria produce spores that can survive for many years in the surrounding environment. In this form, they are inactive but are able to remain infectious for more than 40 years. Clostridium spores are commonly found in soil, saliva, dust, and animal feces (manure). If the spores of the causative bacteria enter the bloodstream of a mammal, they can become active and begin to infect the individual with the bacteria.

PREVALENCE

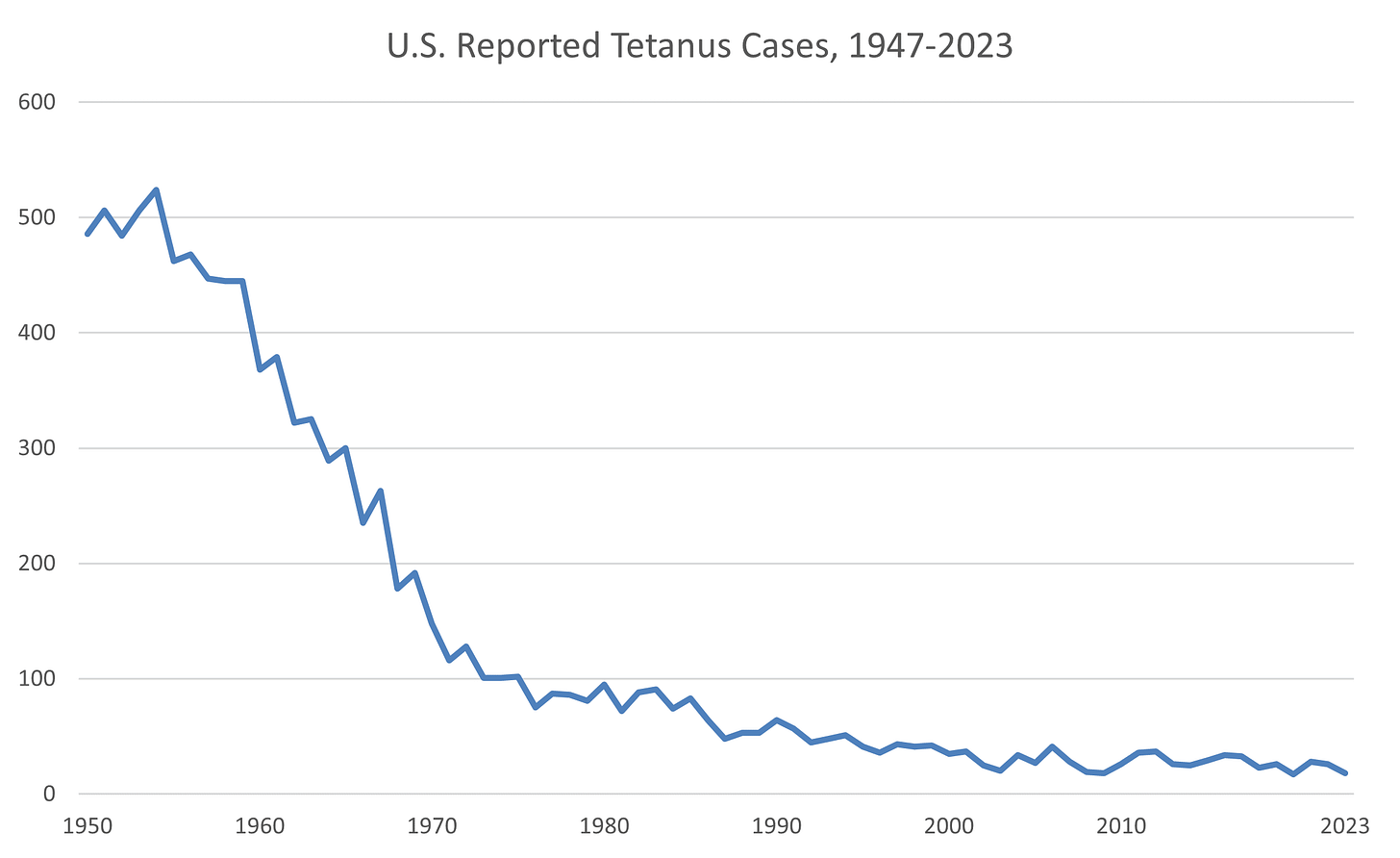

Between 1900 and 1945, before widespread use of the tetanus vaccine began, the mortality rate of tetanus dropped from 2.4 per 100,000 to 0.5 per 100,000 in the population, due to advancements in living conditions, treatment, and health care — a 79% decline.

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/php/surveillance/index.html

Since tetanus became a nationally notifiable disease in 1947, reported tetanus cases have declined more than 95% in the US. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were an average of 43 cases of tetanus reported annually during 1998-2000.

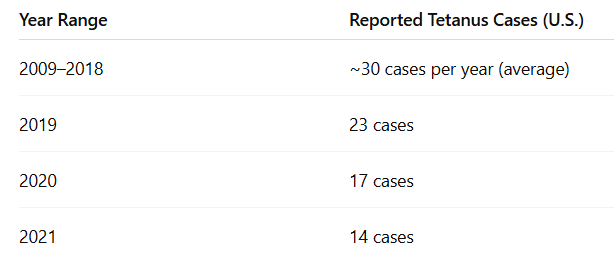

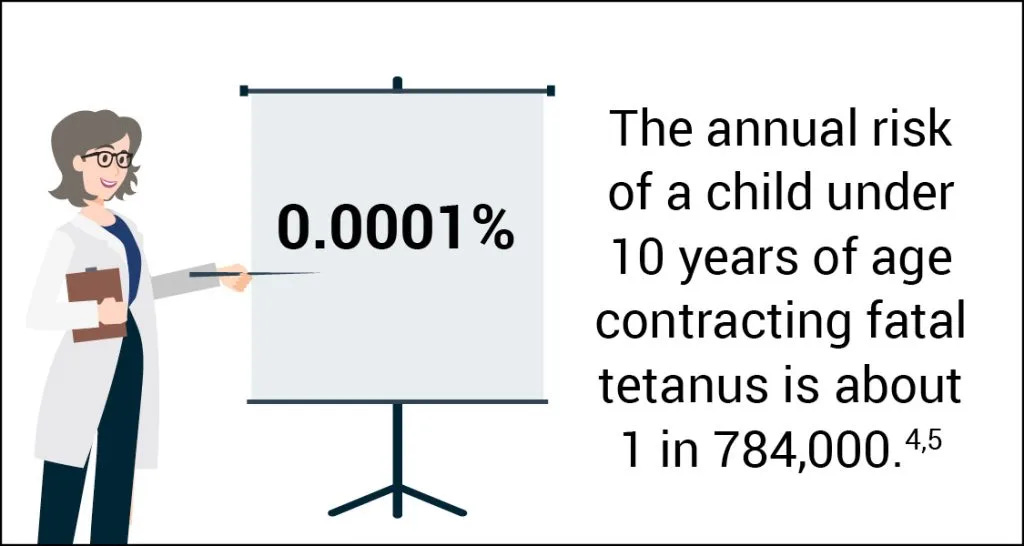

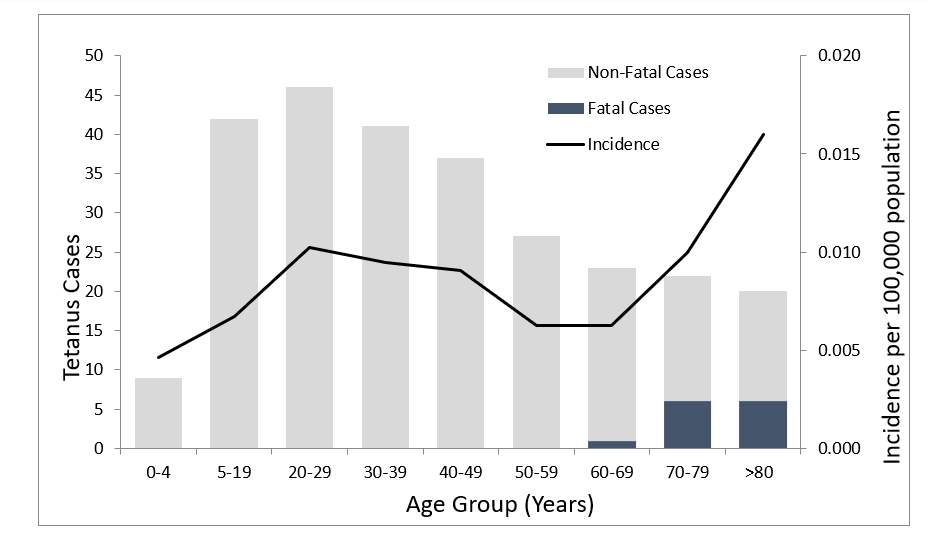

Tetanus among children is uncommon in the US. The highest average annual incidence of reported tetanus was among persons aged >60 years. Beyond age and lack of up-to-date tetanus vaccination status, diabetes, a history of immunosuppression, and intravenous drug use are risk factors for tetanus.

Source: https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/tetanus-dis/

"In fact, you're 10 to 1,000 times more likely to be struck by lightning than to be diagnosed with tetanus and diphtheria in the United States," stated Slifka of Oregon Health & Science University.

How Tetanus Spreads (Spoiler: Not From Mosquitoes)

Tetanus isn’t spread from person to person or by insects. An uncomplicated insect bite — especially from mosquitoes, flies, or ants — is not considered a tetanus-prone wound.

Many people associate rust with causing tetanus, particularly rusty nails. However, the “rust” part is more myth than science. Rust does not play any role in causing tetanus but this link has been made due to the fact that most rusty objects are left outdoors, where the Clostridium tetani bacteria can be found.

The bacteria can enter the body through a deep cut, like those you might get from stepping on a nail, or through a burn.

Tetanus is transmitted when spores of the Clostridium tetani bacterium enter the body through a break in the skin, usually a wound. Contraction of tetanus is through contamination of the wound with soil, due to puncture wounds (nails, splinters, animal bites), wounds entering joints, or through other subsurface wounds (dirty cuts or lacerations from tools, fences, or metal objects), such as surgical incision sites, that were not properly treated.

While insect bites themselves don’t transmit tetanus, scratching the bite can open the skin. If that open wound gets contaminated with soil or dirt, theoretically, tetanus spores could enter. Still, this is very rare, and in healthy people, the risk is close to zero.

PRO TIP: The best way to prevent problems from insect bites isn’t a vaccine — it’s bite prevention (repellent, protective clothing) and good wound care if you scratch or break the skin.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

With the growth and multiplication of bacteria, a toxin begins to be produced that can wreak havoc on the nervous system. It is worth noting that it is the toxin, not the causative bacteria (this will be important to remember when discussing the vaccine), that leads to the effects and symptoms of tetanus.

This toxin binds to nerve endings, disrupting their normal function to relax the muscles and resulting in the contraction of these muscles, particularly in the jaw and neck, and can also affect breathing and swallowing, possibly leading to death (10% to 20% of cases).

It usually takes about 3-10 days for symptoms to become evident after exposure to the bacteria, although the incubation period may be as long as three weeks.

Signs of tetanus may include:

Stiffness of muscles in the jaw

Neck stiffness

Difficulty swallowing

Stomach muscle stiffness

Spasms of muscles

Sweating

Fever

Bloody stools and/or diarrhea

Tachycardia

It is also possible for bone fractures, particularly of the spine, to occur as a result of the tetanus infection and muscular contractions.

POSSIBLE OUTCOMES OF INFECTION

Tetanus can range from a mild illness to a life-threatening emergency, depending on how quickly it’s treated, the patient’s health, and the severity of toxin exposure. In modern healthcare settings with intensive care, about 90% of patients survive.

Without treatment, 25% of people with the infection are likely to die and it is, therefore, imperative that treatment is sought as soon as possible.

From 2013 through 2022, a total of 267 cases and 13 deaths from tetanus were reported in the US through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS).

The age distribution of tetanus cases was as follows:

20% (54 cases) were in individuals 65 years of age or older.

61% (162 cases) were in individuals 20 through 64 years of age.

19% (51 cases) were in individuals younger than 20 years, including one case of neonatal tetanus.

All tetanus-related deaths occurred among patients >60 years of age.

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/surv-manual/php/table-of-contents/chapter-16-tetanus.html

Recovering from tetanus does not make you immune.

TREATMENT

Tetanus is a medical emergency requiring:

Care in a hospital

Immediate treatment with medicine called human tetanus immune globulin (TIG). This injection contains antibodies that neutralize the tetanus toxin still circulating in the body. It’s most effective if given early after symptoms begin.

Aggressive wound care. Removing dirt, debris, and dead tissue helps eliminate the source of bacteria and stop more toxin from being made.

Drugs to control muscle spasms, muscle relaxants (like benzodiazepines) reduce the painful spasms.

Antibiotics (often metronidazole or penicillin) are given to target Clostridium tetani in the wound.

Nutritional support is important because spasms and prolonged illness can cause weight loss and dehydration.

Depending on how serious the infection is, a machine may be required to help the patient breathe. Mechanical ventilation (a breathing machine) may be necessary if chest or throat muscles are affected.

Risks Versus Benefits of DTaP and Tdap

The tetanus toxoid vaccine was first approved for use in the United States in 1924. It was initially introduced as a single antigen vaccine and later combined with other vaccines like diphtheria toxoid and pertussis vaccines. In 1948, whole-cell pertussis vaccine combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid (DTP) was developed, however, adverse events were common; local and systemic reactions reduced the rate of vaccination. Consequently, whole-cell pertussis vaccines were replaced with acellular pertussis (aP) vaccines in the 1990s, which are subunit vaccines containing inactivated components of B. pertussis cells.

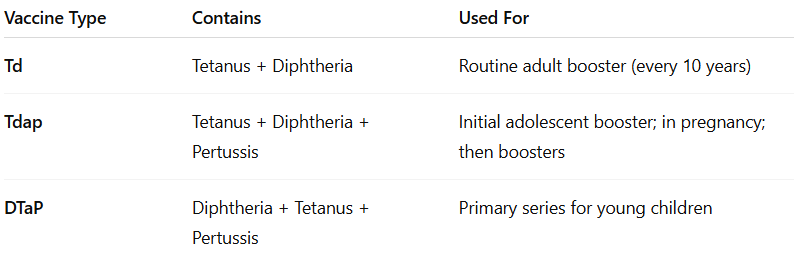

In the US, there is no tetanus-only (monovalent tetanus toxoid) vaccine approved for routine use. Instead, all available options combine tetanus protection with other antigens. Several tetanus-containing vaccines are licensed and recommended for specific age groups and circumstances. Of the 11 vaccines authorized for protection against diphtheria and tetanus, nine also include pertussis, and some are further combined with antigens for additional diseases such as hepatitis B and polio.

DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis) is for children younger than 7, while Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis) and Td (tetanus and diphtheria) are used for older children and adults.

**For the purpose of this analysis particular attention will be given to the DTaP vaccine.**

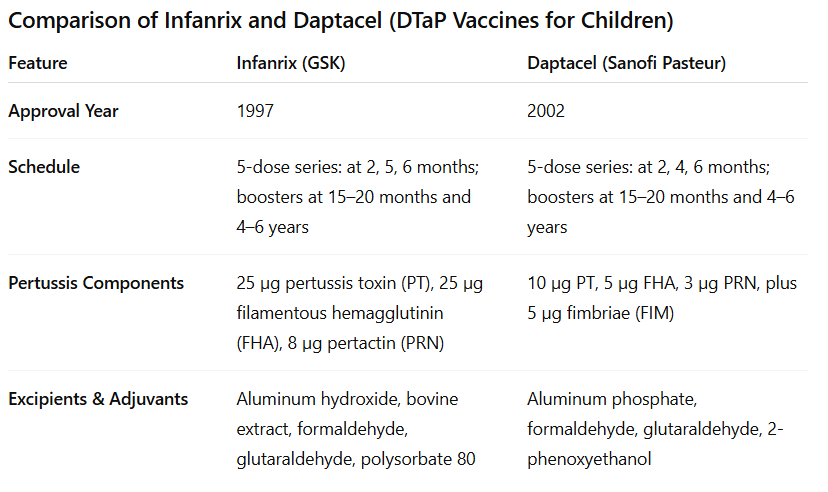

In the U.S., pediatric DTaP vaccines are available under the brand names Infanrix (GlaxoSmithKline), approved in 1997, and Daptacel (Sanofi Pasteur), approved in 2002. Both are commonly used for the full 5-dose childhood series.

ADMINISTRATION AND INGREDIENTS

Infanrix contains higher amounts of pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin compared to Daptacel, while Daptacel includes an additional fimbrial antigen (FIM).

Infanrix contains 10 Lf of tetanus toxoid per dose, which is about twice the amount found in Daptacel (5 Lf per dose).

Both toxins are “detoxified” with formaldehyde.

Both use aluminum-based adjuvants, but the formulations vary—Infanrix uses aluminum hydroxide (formulated to contain 0.5 mg aluminum*) plus bovine extract; Daptacel uses aluminum phosphate (1.5 mg*). They also differ in other excipients like preservatives and stabilizers.

*That means a single 0.5 mg aluminum-containing vaccine dose delivers ~30 to 90 times the FDA's daily IV limit for a 7.3 lb infant — in one injection.

Adverse and severe adverse events following DTaP vaccination

Determining the true rate of adverse events for DTaP is challenging because pre-licensure clinical trials did not include a true placebo control. Instead, participants often received another vaccine or a formulation containing the same adjuvants and excipients as the DTaP shot, minus the antigens. This design makes it difficult to isolate which reactions are attributable specifically to the DTaP vaccine versus shared components, and understates the frequency or nature of vaccine-related adverse events.

That being said, approximately 95,000 doses of Infanrix have been administered in clinical studies. In these studies, 29,243 infants have received Infanrix in primary series studies: 6,081 children have received a fourth consecutive dose of Infanrix, 1,764 children have received a fifth consecutive dose of Infanrix, and 559 children have received a dose of Infanrix following 3 doses of Pediarix. Pediarix is a combination vaccine that contains antigens against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis B, and polio.

In a US study, 335 infants received Infanrix, Energix-B [Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant)], inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV, Sanofi Pasteur SA), Haemophilus b (Hib) conjugate vaccine (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; no longer licensed in the United States), and pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate (PCV7) vaccine (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.) concomitantly at separate sites. Data on solicited local reactions and general adverse reactions were collected for only 4 consecutive days following each vaccine dose.

Approximately 18,000 doses of Daptacel have been administered to infants and children in 9 clinical studies. Of these, 3 doses of Daptacel were administered to 4,998 children, 4 doses of Daptacel were administered to 1,725 children, and 5 doses of Daptacel were administered to 485 children. A total of 989 children received 1 dose of Daptacel following 4 prior doses of Pentacel.

In all the clinical trials with Daptacel, the “control” group received different combinations of DTaP or DTP vaccines, sometimes concurrently with other vaccines as well.

The package insert for Infanrix and Daptacel list warnings for Guillain-Barré syndrome, fainting, seizures in children as well as apnea (temporary cessation of breathing) in infants.

Adverse Events Reported After Approval

Since pre-licensure clinical trials are not always designed to capture the full range of side effects, post-marketing surveillance systems become an important source of safety data.

Common side effects of the DTaP vaccine include fever, loss of appetite, vomiting, and fatigue/weakness.

A more serious potential side effect is seizure, which may occur in about 1 in 683 children vaccinated with DTaP.

According to the package inserts, the following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of Infanrix and Daptacel: Bronchitis, cellulitis, respiratory tract infection, lymphadenopathy, thrombocytopenia, anaphylactic reaction, hypersensitivity, encephalopathy, headache, hypotonia (decreased muscle tone), syncope, ear pain, cyanosis, apnea, cough, angioedema, erythema, pruritus, rash, urticaria, fatigue, injection site induration, injection site reaction, nausea, diarrhea, febrile convulsion, grand mal convulsion, partial seizures HHE, somnolence (sleepiness), and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

VAERS received 50,157 reports involving receipt of DTaP vaccines (Infanrix®, Daptacel®, Pediarix®, Kinrix®, Pentacel®) in the US from January 1, 1991 through December 31, 2016; 43,984 (87.7%) of them reported concomitant administration of other vaccines, and 5,627 (11%) were serious. There were 840 deaths reported to VAERS after receipt of DTaP vaccines during that same time period. Among 725 reports, the most frequent cause of death (350 of 725; 48.3%) was sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) with the predominant age group being infants <6 months of age.

How Effective is DTaP?

Recall that it’s not the bacteria that causes the illness, it’s the toxin. DTaP does not prevent infection with the bacteria because it targets the tetanus toxin. Protection against disease is due to the development of neutralizing antibodies to the tetanus toxin.

Are Adult Boosters Really Necessary?

After a complete DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis) vaccination series in childhood, immunity to tetanus was generally considered to last for at least 10 years. In 1966 the adult booster vaccination schedule was adjusted up from every 5 years to once every 10 years in the US.

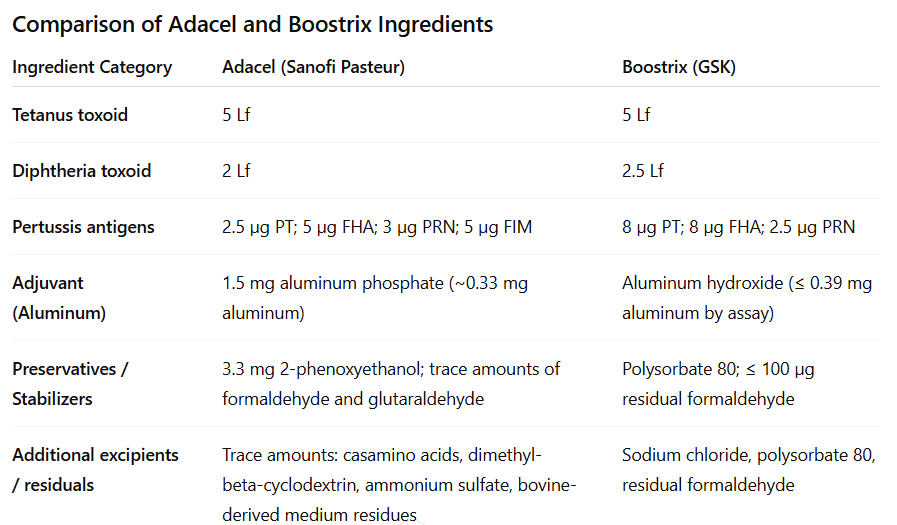

Adolescent and adult formulation (tetanus–diphtheria–acellular pertussis [Tdap]) of vaccines which were licensed for adolescents in 2005 are in use under the brand names as Boostrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Adacel (Sanofi Pasteur) in the United States. Tdap vaccination was recommended for adults younger than 65 years in 2006.

NOTE: TDaP contains lower amount of diphtheria and pertussis antigens than the DTaP vaccine.

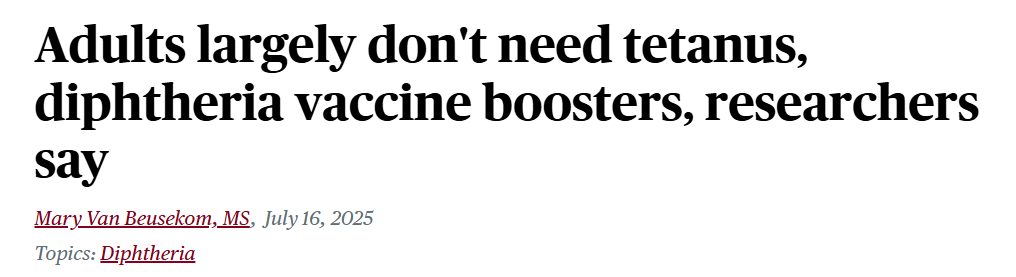

In contrast to the United States, the World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend adult tetanus or diphtheria booster vaccinations for individuals who have completed their childhood vaccination series, and at least 10 European countries do not currently recommend routine booster vaccination for adults.

Researchers examined the incidence rates of tetanus and diphtheria among countries that do or do not recommend adult booster vaccination to determine if adult booster programs provide a benefit over childhood vaccination alone.

Source: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/diphtheria/adults-largely-dont-need-tetanus-diphtheria-vaccine-boosters-researchers-say

Studies the team conducted in 2016 and 2020 suggested that the vaccines generate at least 30 years of immunity against the life-threatening infections, far beyond the current 10-year booster recommendations.

An initial comparison of 2 representative countries provided valuable insight into this question. A review led by by Slifka and colleagues noted that despite France having a 10-year adult booster program and the UK having none for decades, there was no advantage to France’s approach.

Despite a robust adult booster program in France maintained with nearly 80% documented compliance, there was no decline in the incidence of tetanus in comparison with a similarly sized country (United Kingdom) that does not recommend adult booster vaccination. In some cases, the UK even demonstrated slightly better disease control.

To determine if these results were more broadly applicable to other countries, they expanded their analysis to incidence data from 31 North American and European countries. This large-scale study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases examined over 11 billion person-years of data between 2001 and 2016.

The study found no significant difference in tetanus or diphtheria rates between countries that recommend routine adult boosters and those that don’t. Adults do not need tetanus or diphtheria booster shots if they’ve already completed their childhood vaccination series against these rare, but debilitating diseases

These findings align with the World Health Organization, recommending that adult boosters are not routinely needed for individuals who completed the childhood series.

Adult boosters should be considered for emergency use in cases involving susceptible wounds, travelers to areas endemic for diphtheria, and anyone who didn't complete the childhood vaccine series.

BOTTOM LINE: Requiring fewer vaccinations for adults could save the U.S. about $1 billion annually in unnecessary medical costs.

Get DTaP or like if you enjoy allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases.

Interestingly, I had a titer done for Tdap in May of 2024 to try and not have to take another one for nursing school. It came back and showed me as immune to both Tetanus and Diphtheria, but for pertussis, there was no range for immunity. Pertussis result was 1 IU/mL and the results stated this:

"REFERENCE RANGE::

Age (years) (IU/mL)

IgG: < or = 10 <66

11-59 <43

> or = 60 <32

This assay cannot be used to assess protective immunity to

pertussis because the specific antibodies and antibody levels

that correlate with protection have not been well defined.

The primary intent of the assay is to aid in the diagnosis

of infection following natural exposure to Bordetella

pertussis. The indicated PT IgG reference ranges reflect the

90th percentile of antibody levels in sera from healthy

children and blood donors; thus, levels above the reference

range suggest recent infection or vaccination within the

last few months.

This test was developed and its analytical performance

characteristics have been determined by Quest Diagnostics.

It has not been cleared or approved by FDA. This assay has

been validated pursuant to the CLIA regulations and is

used for clinical purposes."

They did not accept my titer and said I still had to have the vaccine every ten years...