The Hidden Dangers of Vaccinating Chickens for Bird Flu

Alternative Solutions for Safeguarding Domestic Poultry from Avian Flu

By now, nearly everyone is aware of the bird flu outbreak affecting poultry in the U.S. In response to the ongoing H5N1 avian flu outbreak, poultry culling (or depopulation) has become a standard measure. This involves killing infected or potentially exposed flocks to curb the spread of the disease, with farmers receiving compensation from the USDA for their losses.

Source: Foam depopulation https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/environmental_health/pdfs/2020-08-25--Emergency-Rulemaking-Petition-to-USDA_Factory-Farm-Depopulation.pdf

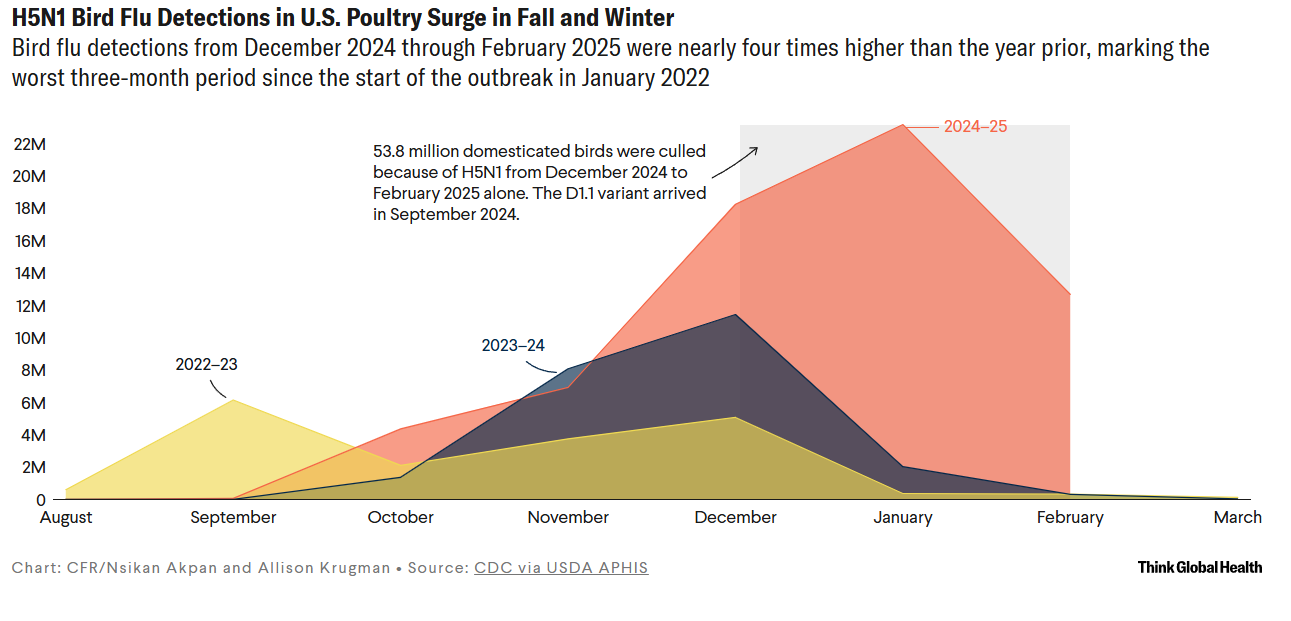

Since H5N1 was first detected in U.S. poultry in early 2022, outbreaks have resulted in the loss of a record 147.25 million birds across all 50 states and Puerto Rico. From December 2024 to February 2025, alone, 53.8 million domesticated birds were culled due to H5N1.

Source: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/us-egg-prices-see-largest-jump-1980-bird-flu-outbreaks-continue

Mass culling of poultry has proven ineffective in stopping the spread of avian flu among flocks. There has been growing advocacy to halt mass culling and transition to large-scale vaccination programs for poultry.

The US is considering vaccinating chickens against bird flu

With egg prices in the United States soaring because of the spread of H5N1 influenza virus among poultry, last month the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) conditionally approved a vaccine to protect the birds.

Source: https://news.zoetis.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2025/Zoetis-Receives-Conditional-License-from-USDA-for-Avian-Influenza-Vaccine/default.aspx

Vaccination can mask infection allowing the silent spread of virus

The reason poultry are not routinely vaccinated is that most vaccines do not prevent infection, and as a result, they don't stop the spread of the virus.

I can speak to this firsthand, as I was part of a research team that developed and tested an H5N3 poultry vaccine (Poulvac FluFend iAI H5N3 RG) designed to protect against the H5N1 influenza virus.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682203004586

(Note: that’s me in the red, I had a different last name at the time)

In 2004, Fort Dodge Animal Health (a division of Wyeth at the time, and later purchased by Pfizer) collaborated with members of St. Jude's Virology Division to develop an avian vaccine to protect against the H5N1 virus, which evolved into a license agreement later that year. The seed stock for the vaccine was made using the plasmid rescue system developed at St. Jude. St. Jude made the seed stock used by Fort Dodge to prepare prototype vaccines within an established seed-lot system to develop Poulvac® FluFend H5N3 RG, a viable large-scale commercial product.

In 2006, Fort Dodge announced the vaccine was conditionally approved by the National Agency of Veterinary Medicine of France for use in controlling the H5N1 avian flu virus spreading in France. The French government then requested 7 million doses of the vaccine to begin its control and eradication program. They began by vaccinating outdoor ducks to prevent them from contracting avian influenza from migrating birds. Fort Dodge continues to promote the use of this vaccine as the best way to protect bird populations from the spread of this deadly virus.

During this study, forty white leghorn chickens were vaccinated subcutaneously with a 0.5 ml volume at the base of the neck at 8 days of age. In the second experiment, 20 of the vaccinated chickens received booster doses of vaccine 4 weeks after the first vaccination by the same method and route. Three weeks after vaccination, chickens were challenged (inoculated) with avian H5N1 virus intranasally. Unvaccinated, uninfected contact chickens were placed in cages with vaccinated challenged birds 1 day later to detect transmission of the challenge virus from vaccinated birds. On day 3 and day 7 after challenge, tracheal and cloacal swab samples were obtained as previously described. Clinical signs were observed for 10 days after challenge.

Although vaccinated birds had high levels of antibodies and showed no disease signs, birds still shed low levels of virus in their feces which transmitted to contact birds.

The testing of the reverse genetics derived vaccine concluded, “Neither the commercial H5N2 vaccine nor the standardized reverse genetics H5N3 vaccine provided sterilizing immunity in chickens; low levels of virus shedding were detected in birds vaccinated with both types of vaccine.”

The study found that several vaccines against the avian H5N1 virus were ineffective at preventing infection or transmission of the virus.

Alternate approaches to curbing influenza infection in poultry

“Let it rip”

There are people advocating for the “let it rip” approach as a response to the avian flu epidemic among domestic poultry. This strategy suggests allowing the virus to spread in poultry flocks to identify and preserve birds that may be naturally immune to the virus. The major issue with this plan is that H5N1 is highly lethal in domestic poultry, causing up to 100% mortality. That is why this subtype of influenza is denoted as “highly pathogenic,” it can wipe out entire flocks within a few days.

Strengthen the immune system with nutritional support

The disease overwhelms birds especially in large-scale poultry operations, where birds can have weaker immune systems. Factory farms are characterized by confining large numbers of animals within relatively small areas. Most factory-farmed chickens are not allowed to spend time outdoors, confined instead to crowded indoor sheds for the vast majority of their lives. In conventional egg production facilities, layer hens are subjected to extreme forms of confinement, including battery cages. Battery cages are designed to allow each bird roughly the same amount of space as a piece of lined paper; birds are prevented from running, walking more than a few steps, and even fully stretching their wings.

One approach that hasn't been widely discussed is improving chicken feed to strengthen the immune system of chickens. On factory farms, chickens' daily diet typically consists of specially formulated feed mixes and routine antibiotic doses. The primary protein source in most poultry diets is soybean meal, a byproduct of soybean processing. Some feeds may also include smaller amounts of animal proteins, such as poultry by-product meal, meat and bone meal, or fish meal, though these ingredients are less common in the diets of laying hens.

The commercial diet for chickens is comprised of different grains, often concentrated on higher protein content for rapid growth. An average broiler chicken diet is composed of 42.8% corn and 26.4% soybeans for protein, and about 14% bakery meal. Egg-laying hens get more corn in their diet, about 53%, and about 30% comes from soybeans and bakery meal. This diet pattern is not healthy or well-balanced.

To boost chickens' immune health, farmers could supplement their diet with probiotics, vitamins (A, D3, E, and B-complex), and electrolytes, as well as offering them fresh greens, vegetables, fruits, and herbs. Probiotics play a vital role in immune health and maintaining the overall health of the flock.

Prophylactically treat chickens with antiviral therapeutics

Another approach would be using antiviral therapeutics to treat infected flocks prophylactically. This would serve to lower the viral load within birds and across the population overall leading to lower transmission rates of the virus.

Although antiviral drugs like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir are effective in treating human infections, they are not currently approved or recommended for use in poultry. Therapeutic drugs should be “intensively” tested on US poultry flocks infected with bird flu.

The USDA has recently announced it will fund up to $100 million for projects exploring prevention, therapeutics, research and potential vaccines to treat bird flu.

One company, Bioxytran* (OTCQB: BIXT) has announced a potential breakthrough in treating Bird Flu (H5N1) in egg-laying chickens through a new water-soluble galectin antagonist currently in preclinical trials. The treatment aims to prevent the need for mass culling during outbreaks by blocking viral entry into cells, neutralizing the virus in egg-laying chickens. This innovative water-soluble galectin antagonist, currently in preclinical trials, could revolutionize how outbreaks are managed in egg-laying chickens, preventing mass culling and safeguarding the global food supply.

“This breakthrough represents a significant step forward in our mission to combat viral diseases,” said David Platt, CEO of Bioxytran Inc. "By targeting the virus directly, we can protect both animal health and the global food supply. Our galectin antagonists block the spike proteins outside the cell. This may stop the spread of the disease right away. Our peer-reviewed study showed that our carbohydrate-based galectin antagonists attach to viral spike proteins. This stops the proteins from connecting to cells. This mechanism is found in all mammals and forms the basis of our research, which should eliminate the risk of possible mutations. Bird Flu outbreaks have devastating economic consequences, costing the poultry industry billions annually. Current protocols require the culling of entire flocks, leading to significant losses for farmers and disruptions in the food supply chain. Our treatment could eliminate the need for such drastic measures, offering a more sustainable solution. We are actively seeking partnerships.”

(*Note: I have no affiliation with this company)

Conclusions: The ongoing H5N1 bird flu outbreak in the U.S. has resulted in costs surpassing $1.4 billion, including $1.25 billion in indemnity and compensation payments. The USDA has also allocated an additional $1 billion to fight the virus and reduce egg prices. Since February 2022, over 166 million birds have died due to bird flu outbreaks, leading to higher egg prices for consumers. Some restaurants have even introduced surcharges on egg-based dishes in response to the shortage.

The traditional approach of mass culling to control bird flu in domestic poultry has proven ineffective in halting or even slowing the spread of avian influenza, highlighting the urgent need for alternative solutions. Vaccination has been proposed as a potential method to control the virus, but currently approved vaccines only mask infections, allowing the virus to spread silently and potentially leading to the emergence of new variants.

A more effective and cost-efficient approach to controlling the spread of avian influenza could involve a combination of enhanced nutrition to boost the immune systems of factory-farmed poultry, alongside prophylactic treatment with antiviral therapeutics. The use of antiviral therapeutics would reduce the viral load both within individual birds and across the population, leading to a lower overall transmission rate.

The bird flu can join the monkey pox, swine fllu and Covid money making coax. Children have natural immunity until it is destroyed by the experimental ‘vaccines’

One would think that non-symptomatic lower shedding would help a little bit toward transmission, but when you see how these birds live, it’s unlikely it will do anything unless it’s neutralizing. One way would be to take apex breeders and attempt selection for stronger immunity…could even CRISPR-mediated suppression of viral life cycle help? It seems like (although a longer process) a natural husbandry approach to select for quantitative resistance traits would be preferred. But we have to remember that vaccination is a big business. You do have to wonder how altering diet could help…considering these diets are optimized for one thing. The crazy part though is “social distancing” 🤣is impossible for these birds and if one gets infected it’s game over. I was trying to argue with a poultry company during an interview that they should care about epigenetics: how much could changing diet and environment of the birds give them a fighting chance to better fight infection? This article was great in that it goes deep in how difficult of a problem this really is.