Weighing the Risks vs. Benefits of the Rabies Vaccine: Essential Insights for Informed Decisions

What You Need to Know to Make an Educated Choice About Rabies Prevention for Your Canine Companion

**This is a long one but be sure to read all the way to the end, especially if you are a pet parent. It will be worth it.**

Rabies Virus is the deadliest virus in the world.

Once symptoms appear, rabies virus infection is 100% lethal.

Source: https://www.labroots.com/trending/microbiology/5761/brief-history-rabies

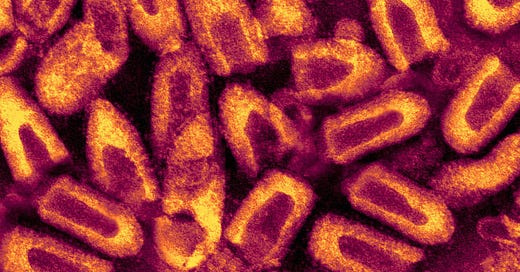

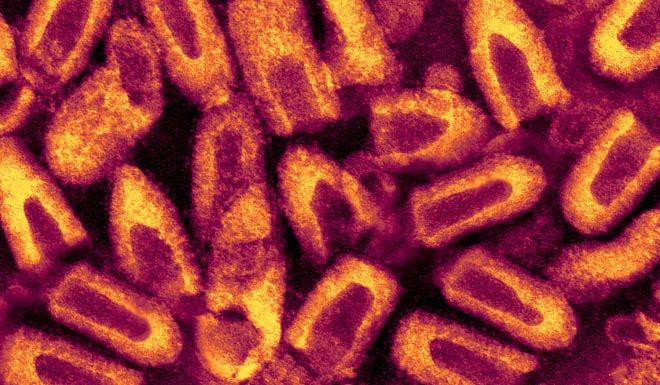

Rabies is caused by the rabies virus. It’s a lyssavirus - a single-stranded, bullet-shaped, enveloped RNA virus.

Fun fact, the genus lyssavirus is named for Lyssa, the Greek goddess of madness, rage, and frenzy. In Greek mythology, Lyssa was the goddess of rage, fury, and rabies, known for driving mad the dogs of the hunter Acteon and causing them to kill their master. Aristotle (4th century BCE) said, “Dogs suffer from the madness. This causes them to become irritable and all animals they bite to become diseased.”

Background on Rabies

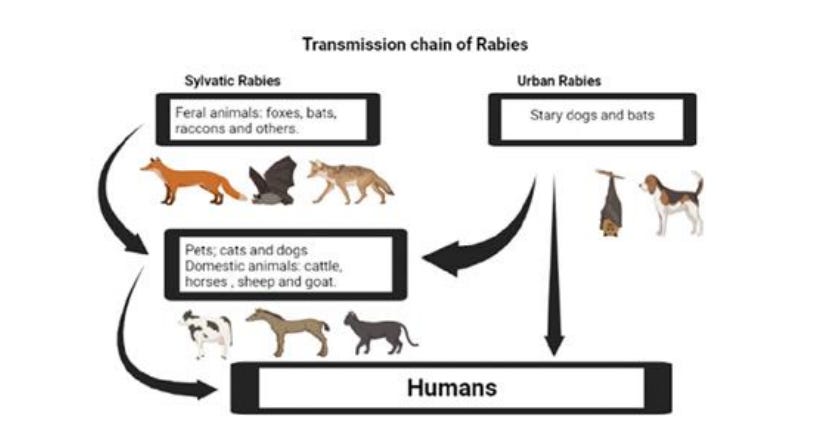

Rabies is a very serious disease that can result in inflammation of the brain and ultimately death. All warm-blooded mammals, including humans can get rabies. Transmission occurs when saliva containing the rabies virus is introduced into an opening in the skin, usually via the bite (or less likely a scratch) of a rabid animal. Wild animals that are most often associated with rabies include skunks, foxes, raccoons, coyotes and bats.

Rabies in dogs has been known since the fifth century B.C. and worldwide the dog has long been known to be a principal transmitter of rabies. In North America, however, bats (more on bats in upcoming blogs) are the most common carriers because pet owners are typically required to vaccinate their animals.

In the U.S., around 4,000 animal rabies cases are reported each year, with more than 90% occurring in wildlife like bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes. Unvaccinated dogs who spend time outdoors, especially around wild animals, are at the greatest risk for contracting rabies. Dogs account for only about 1% of rabid animals reported each year with about 400 to 500 cases of rabies being reported in domestic pets each year.

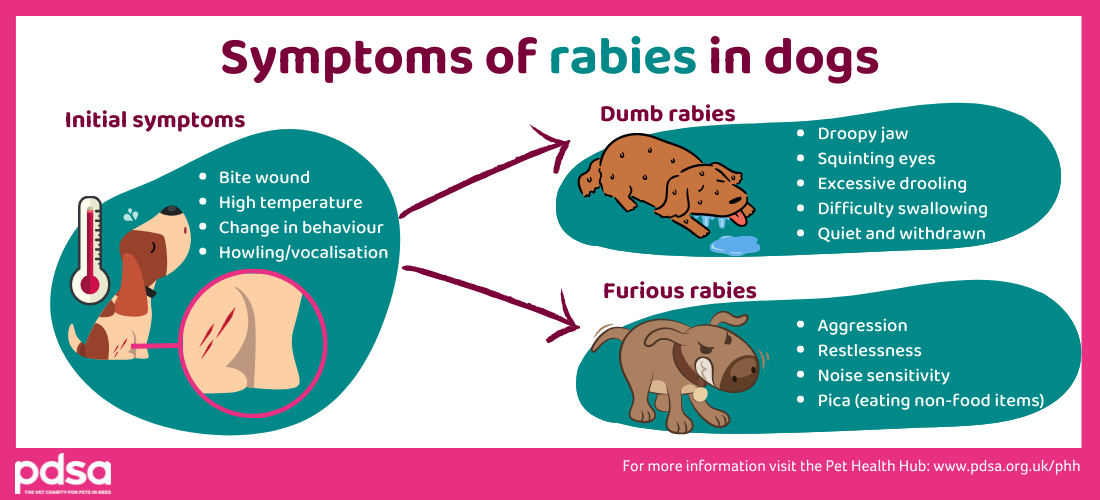

A dog infected with rabies may exhibit the following signs:

Fearfulness

Aggression

Excessive drooling/foaming at the mouth

Difficulty swallowing

Confusion/disorientation

Difficulty moving/paralysis

Dilated pupils or vacant stare

Abnormal behavior (i.e. a wild animal who does not shy away from people)

The incubation period is related to the distance between the bite site and the brain, wound severity and amount of virus. Symptoms of rabies usually take 2-8 weeks to develop after the bite, but in some rare circumstances, it can take up to a year.

Early symptoms include:

Fever (high temperature)

Changes in behavior

Howling or yelping

Licking or chewing the bite wound

Rabies can then develop in one of two ways, ‘dumb rabies’ (most common) or ‘furious rabies’.

Source: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/pet-help-and-advice/pet-health-hub/conditions/rabies-in-dogs

There are no available tests for rabies in live patients, so vets have to diagnose it based on symptoms, travel history, and whether the dog was seen being bitten by another animal. Definitive diagnosis is done using a post-mortem antibody test. This means that the test can only be performed on animals after they have died or been euthanized.

The best, and the only way to prevent rabies in dogs is to vaccinate against it.

In several countries around the world, canine rabies was greatly reduced by mass immunization of dogs.

In the United States the canine strain of rabies was eliminated in 2007.

"The elimination of canine rabies in the United States represents one of the major public health success stories in the last 50 years," former CDC Director Dr. Julie Gerberding said in a statement.

The first rabies vaccine was developed by Pasteur in the early 1880s when he adapted “street” virus to rabbits by serial intracerebral passage (Pasteur, 1885). This was mainly used for humans.

Inactivated virus vaccines for dogs prepared from infected brain suspensions became available in the 1920s. The development of live attenuated rabies virus, vaccines in low egg passage (LEP) and high egg passage (HEP) (Koprowski, 1954) led to effective vaccination of dogs (Tierkel et al., 1953; Sikes, 1975). However, on rare occasions the live attenuated vaccines caused rabies-like disease in dogs and are no longer available.

Greatly improved inactivated virus vaccines prepared from rabies virus grown in diploid cell culture are now commonly used in dogs.

Annual vaccination for rabies increases risk of adverse events for pets.

According to one study, the rabies vaccine had the highest rate of adverse events among individual vaccines. Rabies vaccines cause a multitude of adverse effects. These range from immediate reactions to long term, chronic illness, and even death. Anaphylactic (or allergic) reactions are amongst the most severe reactions that can be seen after vaccination. The signs may be facial swelling, itching, weakness, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, shock and death.

Documented reactions include:

Behavior changes (aggression, separation anxiety)

Obsessive behavior, self-mutilation, tail chewing

Pica – eating wood, stones, earth, stool

Destructive behavior, shredding bedding

Seizures, epilepsy

Fibrosarcomas at injection site

Autoimmune diseases of bone marrow and blood cells, joints, eyes, skin, kidney, liver, bowel or central nervous system

Muscular weakness and or atrophy

Chronic digestive problems

One veterinarian recommends…

Animals that have had anaphylactic reactions should be treated beforehand with antihistamines if vaccination is mandatory. To further minimize the risk, avoid using vaccines with multiple antigens, use modified live instead of killed vaccines, make certain the vaccine is not injected into the vein, and use subcutaneous or intranasal vaccines instead of intramuscular ones if possible.

If multiple doses of vaccines are administered to small-breed dogs (<10 kg), this may increase the risk of adverse reactions. Therefore, it is best to give only one vaccine at a time.

Annual re-vaccination recommendation on the vaccine label is just that.

Some rabies vaccinations are licensed for one year, others are labeled for three years, but some states require annual vaccinations regardless of labeling. Actually, three-year rabies vaccinations are the same as one-year vaccinations. There is no additional volume or disease agent administered to trigger an immune response; the labeling is simply different for the vaccinations.

Although your pet may receive a vaccination labeled for one year and is technically protected for three years, she is not legally protected for three years in the eyes of the state. Therefore, protection based on vaccination is a legal definition and not based on actual immune status. The annual revaccination recommendation on the vaccine label is just that: a recommendation without the backing of long term duration of immunity studies.

Veterinary immunologist Dr. Ronald Schultz states: “There is no benefit from annual rabies vaccination and most one year rabies products are similar or identical to the 3-year products with regard to duration of immunity and effectiveness. However, if they are 1 year rabies vaccines, they must be legally given annually! Rabies vaccine is the only canine vaccine requiring a minimum duration of immunity study. However, revaccination annually does not necessarily improve immunity. However, annual vaccination does significantly increase the risk for an adverse reaction in the dog.”

Most of the inactivated rabies virus vaccines on the market today induce immunity in dogs that lasts for 3 years. Scientific data suggest that commercial rabies vaccines confer durations of immunity well beyond 3 years, and that vaccinating dogs against rabies triennially, as nearly all American states require, is unnecessary. From challenge trials, the duration of immunity for regular vaccines has been shown to be seven to nine years, if not longer.

In 1992, Aubert demonstrated in France that dogs remained immune to a rabies virus challenge 5 years after vaccination. The serological studies of Schultz and Schultz and Conklin showed that immunity to rabies virus was present 7 years after vaccination.

According to a study by the Rabies Challenge Fund, scientific data suggests that immunity to rabies in vaccinated dogs can last longer than three years. A prospective study of 65 research beagles kept in a rabies-free environment was undertaken to determine the duration of immunity after they received licensed rabies vaccines. The eventual goal was to extend mandated rabies booster intervals to 5 or 7 years and help reduce the risk of vaccine-associated adverse events.

The study demonstrated that i) duration of immunity to rabies in vaccinated dogs extends beyond 3 years; ii) immunologic memory exists even in vaccinated dogs with serum antibody titer < 0.1 IU/mL; and iii) non-adjuvanted recombinant rabies vaccine induces excellent antibody responses in previously vaccinated dogs 14 days after administration.

The bottom line was that protection from rabies persists without annual or triennial re-vaccination.

Recommendations based on available science-based evidence

Given all this information, vaccination especially re-vaccination should be based on risk versus benefit for companion animals. That being said because the outcome of contraction of rabies infection is particularly devastating, I believe the benefit of vaccination outweighs the risk of adverse effects. This is why I chose to give my new puppies the rabies vaccine however, I made sure to ask for the thimerosol-free (adjuvant-free) rabies vaccine to help reduce the chance of a adverse reaction.

What about re-vaccination? A significant number of practitioners believe the annual revaccination recommendation on the vaccine label is evidence the product provides immunity for (only) one year. Again, this is simply not true. Some vets have suggested that giving a vaccine annually that has a duration of immunity of 3 or more years provides much better immunity than if the product is given only once during the three years. This is simply not true because many practitioners really don’t understand the principles of vaccinal immunity.

Again, re-vaccination should be about risk versus benefit. The role dogs play in our lives have changed dramatically over the last hundred years. They are no longer left outdoors to guard our homes and livestock, or used just for hunting, they have become part of our families and for some are our surrogate children. Therefore, are my little couch potato, pampered fur babies at risk of contraction of rabies virus? Are they outside all day? Do they have contact with wild animals? Did my 18 year old geriatric fur kid have any risk of contracting rabies?

I would contend that in these instances the risk far outweighs any benefit they may receive from annual vaccinations. If a vaccine is given that is not needed and it causes an adverse reaction that is unacceptable and very costly.

We need more reasonable regulations and protocols, based on science and not just fear.

Exemptions for rabies vaccination

Nineteen US States now allow medical exemptions in lieu of rabies vaccination.

Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin.

Each state’s law is different, but in most cases, it means your vet can write an exemption for a pet who isn’t healthy enough to be vaccinated.

One state (Hawaii) has no laws or regulations that require vaccination on a statewide basis. Nine states only require rabies vaccinations for IMPORTED animals above a certain age (usually 3 months old).

If your state doesn’t already allow exemptions, think about whether you’d like to get involved and help make changes.

hello Jennifer, please is this true?: https://rumble.com/v5cl4yr-dr.-tom-cowan-on-the-truth-behind-virus-isolation.html it is a short video, I can not believe this