Varicella Vaccine for Kids and Adults: Benefits, Risks, and Science You Should Know

Is the Varicella Vaccine Worth It? A Scientific Perspective

Having conducted an in-depth analysis of shingles and the Shingrix vaccine, it is now important to examine its precursor—chickenpox—and compare it to the Varicella (Varivax) vaccine.

Disclaimer: I am not a licensed healthcare provider or medical professional. I do not offer medical advice. For any medical concerns or questions, please consult a qualified healthcare professional.

SUMMARY OF FACTS:

Chickenpox

Chickenpox is a common childhood illness that is mild in nature.

In adults the illness can cause severe complications.

The rash lasts approximately 4 to 7 seven days and people resume normal activity.

Treatment consists of resting, drinking plenty of water and over-the-counter antihistamines to control itching.

Death is extremely rare and usually only occurs among the elderly.

Upon recovery, immunity is lifelong.

VZV can establish latency in the central nervous system and reactivate later in life as shingles.

Varivax VZV Vaccine

Varivax contains a live, attenuated varicella virus that is prepared using aborted fetal cell lines.

Introduction of Varivax in 1995 has led to an approximate 90% decline in VZV infections and subsequent reduction in hospitalizations due to VZV complications.

Given that Varivax is a live virus vaccine, people who receive the vaccine are still at risk of severe chickenpox infection. The vaccine-strain virus can cause disease in those receiving the vaccine and the vaccine-strain virus can transmit to others.

Similar to wild-type VZV, the vaccine virus can reactivate later in life and cause shingles.

Deaths have occurred following administration of Varivax with over half of those being reported in children under the age of two.

The length of immunity from Varivax is unknown.

Chickenpox Explained: Causes, Complications, and Care

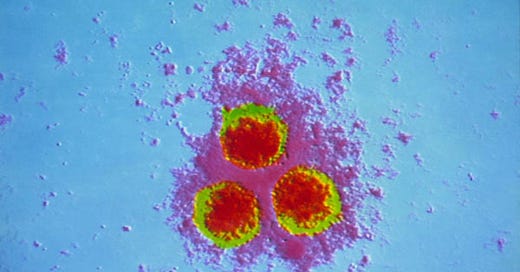

Source: https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/slideshow/slides/varicella-zoster-virus/

Chickenpox, a highly contagious disease, is historically a common childhood illness. Although there are references to chickenpox dating back to ancient times, the virus was first isolated by virologist Thomas Weller in 1954. Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is caused by the the alpha herpesvirus varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

More than 95 percent of American adults have had chickenpox and about 4,000,000 people get chickenpox every year. Prior to 1995, approximately 90% of all cases occurred among children younger than age 15 years, and approximately 39% of all cases were among children between the ages of 1 and 4. Adults 20 years old or older accounted for only 7% of cases.

Transmission

VZV is spread through the air via respiratory droplets (coughing, sneezing) or by direct contact with the rash, particularly the fluid from the blisters.

People are contagious 1-2 days before the rash appears and until all blisters have crusted over.

Chickenpox has an estimated R0 (indicates how contagious an infectious disease is) ranging from 8.5 to 12. This suggests that, on average, one person with chickenpox can infect between 8 and 12 others in a susceptible population.

Signs and symptoms

Chickenpox typically develops 10-21 days after exposure and begins with symptoms which include fever, fatigue, headache. Loss of appetite is also common.

The classic symptom of chickenpox is a rash that turns into itchy, fluid-filled blisters that eventually turn into scabs. The rash may first appear on the head, chest, and back, and then spreads to the rest of the body, including inside the mouth, eyelids, or genital area. It usually takes about one week for all of the blisters to become scabs.

Source: https://hail.to/lyttelton-primary-school-te-kura-tuatahi-o-hinehou/article/GKRfaSf

The illness usually lasts about 4 to 7 days and the rash often lasts about 5 to 10 days. After recovery from infection, VZV can establish latency in the cranial nerve and dorsal root ganglia. VZV then can later reactivate years later as shingles (herpes zoster).

Read here for more information on shingles:

Once a person has had chickenpox, they have lifelong immunity.

Possible Outcomes of VZV Infection

The disease is by and large mild in healthy children. Adults generally experience more severe symptoms compared to children. Chickenpox can cause more serious symptoms in adults over 18.

While often mild, complications can include bacterial infections of the skin, pneumonia, dehydration, encephalitis, and in rare cases, death. Adults and individuals with weakened immune systems are at higher risk of severe complications.

Overall, the death rate from chickenpox is very low, especially in developed countries.

Factors that can increase the risk of death from chickenpox include:

Age: young children and adults over 50 are at higher risk.

Weakened immune system

Underlying medical conditions, such as pneumonia or skin disorders

In the early 1990s, about 4 million people got chickenpox, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized, and 100 to 150 died each year.

Since 1995 an estimated 100,000-150,000 cases of chickenpox occur annually, with fewer than 30 deaths in the US. This translates to a death rate of less than 0.02%.

A total of 155 suspected varicella deaths were reported to CDC during 1996–2013 from 34 states. After review of the records, 83 deaths were classified as likely due to varicella. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection was laboratory confirmed in 57% (n = 47) of deaths. Five deaths reported to CDC occurred among persons who had received varicella vaccine, all were in children (age range 4–15 years) had received 1 dose of vaccine >42 d before rash onset.

During 2008–2011, varicella was listed as the underlying cause of death in 69 records (annual average: 17) and as the contributing cause of death in 65 records. Among deaths for which varicella was the underlying cause of death, 71% were in persons aged ≥50 years; 5 (7%) had cancer.

Treatment

Chickenpox will go away on its own in a week or two. Care of patients with chickenpox consists mainly of ensuring adequate intake of fluids, bed rest, and fever control.

Use non-aspirin medications, such as acetaminophen to relieve fever from chickenpox. Do not use aspirin or aspirin-containing products to relieve fever from chickenpox, as giving aspirin-containing products to children with chickenpox has been associated with Reye’s syndrome, a severe disease that affects the liver and brain and can cause death.

An over-the-counter (OTC) form of antihistamine can help with itching. Calamine lotion and cool colloidal oatmeal baths may also help relieve some of the itching. Keeping fingernails trimmed short may help prevent skin infections caused by scratching blisters.

Adults who are at risk for severe symptoms or who have certain medical conditions may benefit from antiviral drugs.

Risks v. Benefits of the Shingles Vaccine

The chickenpox vaccine was developed in Japan in the 1970s by Dr. Michiaki Takahashi. It was licensed for general use in Japan and Korea in 1988. In the US, there are two licensed chickenpox vaccines. One contains only VZV (Varivax) and the other one is a combination with MMR (ProQuad). The Varivax varicella vaccine was introduced in the US in 1995.

**For the purposes of this analysis, particular attention will be given to the Varivax varicella-zoster virus (VZV) vaccine.**

Implementation of the varicella vaccination program in 1995 in the US led to ∼90% decline in varicella incidence and severe outcomes such as hospitalizations and deaths during the first decade.

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/museum/education/newsletter/2023/nov/index.html

In the United States, varicella (chickenpox) vaccination coverage is high. In 2007 at least 90% of children aged 19-35 months had received one dose, according to the CDC. By 2020, for adolescents aged 13-17 years, the coverage for two doses is also high, with 92% having received two doses and without a prior history of varicella.

Administration

Varivax was licensed for use in people 12 months or older and is administered as a 0.5-mL dose by subcutaneous injection into the outer aspect of the upper arm (deltoid region) or the anterolateral thigh.

The original varicella vaccine was initially licensed in 1995 as a single dose was for routine childhood vaccination. However, outbreaks continued, prompting the need for a second dose. Studies showed that the effectiveness of the first dose was not consistently high, and a second dose was recommended to improve protection and reduce outbreaks. The CDC changed its recommendation for varicella (chickenpox) vaccine to a two-dose schedule in 2006.

CDC recommends two doses of chickenpox vaccine for children, adolescents, and adults who have never had chickenpox and were never vaccinated.

Some people should NOT get chickenpox vaccine, or they should wait.

Have HIV/AIDS or another disease that affects the immune system, are being treated with drugs that affect the immune system for 2 weeks or more, have any kind of cancer, are getting cancer treatment with radiation or drugs, recently had a transfusion or were given other blood products, or are pregnant or may be pregnant.

Children under the age of 13 should get one dose between ages 12 months and 15 months and a second dose between the ages of 4 and 6. Those 13 or older should get two doses at least 28 days apart.

NOTE: Avoid use of aspirin or aspirin-containing products in children and adolescents 12 months through 17 years of age for six weeks following vaccination with Varivax because of the association of Reye syndrome with aspirin therapy and wild-type varicella infection.

Ingredients

The Varivax vaccine contains a live, weakened varicella-zoster virus (1350 plaque-forming units (PFU) of Oka/Merck varicella virus) as its active ingredient. The virus for the vaccine was initially obtained from a child with wild-type varicella, then introduced into human embryonic lung cell cultures, adapted to and propagated in embryonic guinea pig cell cultures and finally propagated in human diploid cell cultures (WI-38). Further passage of the virus for varicella vaccine was performed at Merck Research Laboratories (MRL) in human diploid cell cultures (MRC-5).

NOTE: WI-38 is a human diploid cell line derived from the lung tissue of a 3-month-old female fetus. The fetus was obtained from a legal abortion in Sweden in 1962.

Inactive ingredients include sucrose, hydrolyzed gelatin, sodium chloride, monosodium L-glutamate (MSG), sodium phosphate dibasic, potassium phosphate monobasic, potassium chloride, and residual components of MRC-5 cells (including DNA and protein). Trace quantities of neomycin (antibiotic) and bovine calf serum may also be present.

MRC-5 cells are a human diploid cell line, specifically a fibroblast cell line derived from the lung tissue of a 14-week-old male fetus in 1966.

Source: https://www.atcc.org/products/ccl-171

Adverse and severe adverse events following Varivax vaccination

Clinical Trial Data

In clinical trials (2-9), VARIVAX was administered to over 11,000 healthy children, adolescents, and adults.

In clinical trials involving healthy children monitored for up to 42 days after a single dose of Varivax, fever, injection-site complaints, or varicella-like rashes (chickenpox) were reported.

Other reported adverse events included: upper respiratory illness, cough, irritability/nervousness, fatigue, disturbed sleep, diarrhea, loss of appetite, vomiting, otitis, diaper rash/contact rash, headache, teething, malaise, abdominal pain, other rash, nausea, eye complaints, chills, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, lower respiratory illness, allergic reactions (including allergic rash, hives), stiff neck, heat rash/prickly heat, arthralgia, eczema/dry skin/dermatitis, constipation, itching.

Pneumonitis and febrile seizures were also reported. Seizures may occur in about 1 in 940 vaccinated children.

Nine hundred eighty-one (981) subjects in a clinical trial received 2 doses of Varivax three months apart and were actively followed for 42 days after each dose. Similar adverse events were reported after two doses as were reported in the single dose trial.

Adverse Events Reported After Approval

The following additional adverse events, regardless of causality, have been reported during post-marketing use of Varivax: anaphylaxis (including anaphylactic shock) and related phenomena such as angioneurotic edema, facial edema, and peripheral edema, necrotizing retinitis (in immunocompromised individuals), aplastic anemia; thrombocytopenia (including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)). encephalitis; cerebrovascular accident; transverse myelitis; Guillain-Barré syndrome; Bell's palsy; ataxia; non-febrile seizures; aseptic meningitis; meningitis; dizziness; paresthesia, pharyngitis; pneumonia/pneumonitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; erythema multiforme; Henoch-Schönlein purpura; secondary bacterial infections of skin and soft tissue, including impetigo and cellulitis.

Cases of encephalitis or meningitis caused by vaccine strain varicella virus have been reported in immunocompetent individuals previously vaccinated with Varivax months to years after vaccination. Reported cases were commonly associated with preceding or concurrent herpes zoster rash.

Severe Adverse Events

From 2007 to present, 80 deaths following Varivax vaccine have been reported to VAERS with over half (49) were in the 1 to 2 year old age group. However, VAERS is a passive reporting system — authorities do not actively search for cases of vaccine injury and do not actively remind doctors and the public to report cases. As few as 1% of serious side effects from medical products are reported to passive surveillance systems. These limitations can lead to significant underreporting of vaccine injury.

Due to Varivax being a live virus vaccine, varicella (vaccine strain) infection has been noted to occur. Post-marketing experience suggests that transmission of vaccine virus may occur between healthy vaccinees who develop a varicella-like rash and healthy susceptible contacts. The Institutes of Medicine also found that the “evidence convincingly supports a causal relationship between varicella vaccine and vaccine-strain viral reactivation.” Therefore, similar to natural infection with varicella, vaccine-strain virus can be reactivated and cause herpes zoster (shingles).

How long does immunity from Varivax last?

The duration of protection of Varivax is unknown.

No placebo-controlled trial was carried out with Varivax using the current vaccine (read that again). A placebo-controlled trial was conducted using a formulation containing 12.5 times VZV per dose than the current vaccine. During the second year of this trial, when only a subset of individuals agreed to remain in the blinded study, 96% protective efficacy was calculated for the vaccine group as compared to placebo.

Several studies have shown that people vaccinated against varicella had antibodies for at least 10 to 20 years after vaccination. But, these studies were done before the vaccine was widely used and when infection with wild-type varicella was still very common.

A case-control study conducted from 1997 to 2003 showed that 1 dose of varicella vaccine was 97% effective in the first year after vaccination and 86% effective in the second year. From the second to eighth year after vaccination, the vaccine effectiveness remained stable at 81 to 86%. The vaccine's effectiveness in year 1 was substantially lower if the vaccine was administered at younger than 15 months (73%) than if it was administered at 15 months or older.

Is the Varicella “vaccine” safer than the chickenpox?

It has not been proven that the varicella vaccine is safer than varicella.

Source: https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/varicella-vrs/

One of the side effects of Varivax is a varicella-like rash, chickenpox. Some people who have been vaccinated against chickenpox can still get the disease. However, they usually have milder symptoms with fewer or no blisters (or just red spots) and mild or no fever. They are also sick for a shorter period of time than people who are not vaccinated. But some vaccinated people who get chickenpox may have disease similar to unvaccinated people.

Given that routine typing of VZV virus is not done to differentiate between infection with wild-type strains and vaccine-strain virus it is difficult to estimate the number of chickenpox cases that are caused by the vaccine-strain.

CONCLUSION:

A significant point to reflect on following this analysis is the unintended shift in disease burden caused by the introduction of the Varivax vaccine. While it has successfully reduced childhood cases of chickenpox, it has also led to an increase in adult cases, particularly among those aged 20 and older—an age group more vulnerable to severe illness and complications.

In addition, vaccinating one-year-olds against chickenpox has temporarily nearly double the incidence of shingles in the wider population, and in younger adults (31-40 year olds) than previously thought. Re-exposure to VZV boosts immunity to shingles, caused by the same virus. Widespread chickenpox vaccination has reduced the opportunities for adults who experienced chickenpox as a child, being re-exposed to the virus. The absence of this natural boosting can potentially leading to increased shingles susceptibility in certain age groups. Thus, many countries have avoided introducing universal chickenpox vaccination in children because it was previously predicted that the reduction in chickenpox related disease would be outbalanced by the temporarily increase in shingles-related disease. Models predict that this increase in shingles incidence could last for 30-50 years and primarily affect individuals who were 10-44 years old when the vaccine was introduced.

A final point to consider is that, historically, chickenpox-related mortality was most prevalent among the elderly population. Although the Varivax vaccine has led to a substantial decline in overall disease-related deaths, it is associated with the rare but serious occurrence of vaccine-related fatalities in pediatric patients.

Considering the outlined risks of chickenpox and the associated benefits and potential side effects of the varicella “vaccine”, you are now prepared to make a well-informed decision regarding the Varivax vaccination.